Alaskan coastal communities adapt as ice turns to water

A new project working with indigenous communities in Alaska aims to make them more resilient as melting sea ice and thawing permafrost threatens their land and way of life.

I

n Arctic Alaska temperatures are estimated to be rising two to three times faster than in the mainland US. For indigenous communities, the water quality, infrastructure and natural ecosystems that help sustain them are threatened by the thawing permafrost, which weakens the ground beneath homes and undermines traditional methods of storing food in underground ice cellars.

“Together with permafrost thawing, sea levels rising, and declining sea ice cover, extreme storms are rapidly eroding some Alaskan coasts and damaging community infrastructure, livelihoods and cultural heritage,” says Guangqing Chi, an associate professor of rural sociology and demography and public health sciences at Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences.

“The rising temperatures are also causing sea ice to melt, disrupting marine food chains that many rural Alaskan communities rely on.”

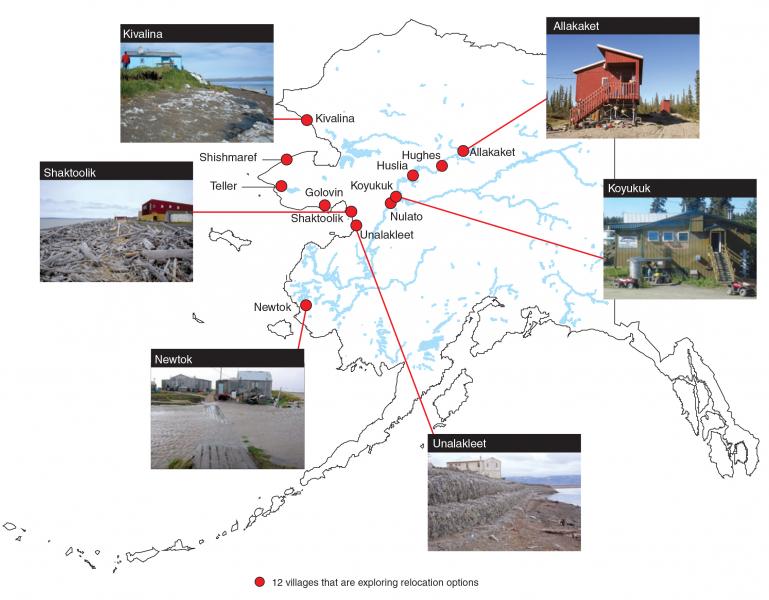

In western Alaska, many communities first formed along a river near the Bering Sea. Melting sea ice means their coastal protection is disappearing. Overall, more than 87% of Alaska’s indigenous communities feel the effects of coastal and river erosion. Some have been forced to partially or completely relocate, such as the village of Newtok which aims to relocate to a site nine miles away at a total cost of approximately $100 million.

Source: United States Government Accountability Office

To better understand the threats from climate change faced by indigenous communities and to help them devise new ways to adapt, a new $3 million grant has been issued by the National Science Foundation (NSF) to Penn State researchers. The money will fund the POLARIS project – “Pursuing Opportunities for Long-term Arctic Resilience for Infrastructure and Society” – as part of the NSF’s Navigating the New Arctic programme as it documents the biological, physical, chemical and social changes occurring in the region.

Crossing disciplines

The POLARIS project wants to work with indigenous communities experiencing or with foreseeable climate change challenges and help them become more resilient. It will involve the study of community disruptors due to environmental change, food in complex adaptive systems, and migration and community relocation as a result of climate change. Alongside research, it will also focus on education, outreach, community engagement and international collaboration.

“A holistic picture of coastal communities has not been developed, nor are ways to effectively address the complex and interconnected problems communities face,” says Chi, who is a principal investigator for the project.

“Solutions will require a transdisciplinary, convergent approach where researchers from different disciplines collaborate to create new knowledge beyond discipline-specific perspectives.”

Village leader Anna Oxereok and three-year-old Frank Komonaseak met by US Air Force officers. Photo courtesy US Air Force

Data and education key

To build a more holistic picture, researchers will analyse data from the Census Bureau and existing surveys of local communities, as well as collecting new data. The hope is that the data will suggest how communities can become more resilient to change and how others can be helped to adapt.

“Ultimately, the project is aimed at synthesizing possible ‘navigation pathways’ for communities as they adapt to rapidly changing social and environmental systems,” says team member Erica Smithwick, professor of geography and associate director of the Institutes of Energy and Environment at Penn State.

The initiative will support local educators working with the communities to develop ways of engaging students, in particular those aged between 17 and 19. Based on interdisciplinary research, it will also train junior researchers, graduate students and undergraduates in this field.

“This will ensure that the rising generation of researchers is well prepared to continue the crucial work to address these issues,” says Chi.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.